by Nitsa Anastasiades

April, 2025

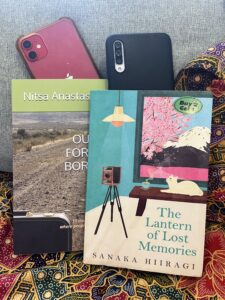

Finishing The Lantern of Lost Memories I’d picked up as a buy 2 get 1 in City Mall Bahrain’s Virgin Megastore book section, this was the question that came to my mind. Well, it popped up twice – once, a third of the way in, and again with a few pages to go.

The book has 3 linked stories: ‘The Old Lady and the Bus’, ‘The Hero and The Mouse’, with ‘Mitsuru and The Last Photo’ as its grand finale.

You must imagine a photo studio in Tokyo with plain, white walls, a pale chaise longue, tea cups, clear tea, the dark room where photos are developed and a courtyard outside, visible from the window with cherry blossoms, pink, against a million different cameras guests passing through this space must choose to go back in time with to take one last photo of their favorite memory.

Death and the afterlife, particularly, have intrigued humans for generations, indeed as far back as the neanderthals, whom archeologists discovered buried their fellow men, according to Karen Armstrong, author of A Short History of Myth, with sacrificial animal bones, weapons and tools, suggesting a sentiment, understanding or yearning to add more value and meaning to a life just ‘lived’.

In this book, The Lantern of Lost Memories, an ex-nursery teacher, very old, must look through hundreds of her photos first, and choose just 92– one for every year of her life (delivered to Hirasaka, who runs this operation), which will be placed on a lantern and spun, sending her to the afterlife with fond memories and in a ‘happy’ state.

An ex-bandit, who’s just been stabbed in the back, in the second story, passes through the studio next, followed by a tormented child, Mitsuru, bruised and beaten by her violent parents.

In all cases, the deceased, having chosen a photo for every year of their long, medium and short lives, must in addition pick one memory they wish to revisit and live again with Hirasaka, as viewing ghosts, and retake a last memorable photo, before returning to the studio to watch the lantern of their lives spin in front of them, as the blinding light sends them on their way.

Pretty, eh?

And it’s not just the pale green and pink cover, the camera, cat, window, blossom, tree and mountain book’s cover with tea cup and lamp, in your hands, smooth, welcoming, before you open it. Or Sanaka Hiiragi’s, the author’s back picture, in kimono and glasses, clutching a file, expressionlessly looking ahead, box framed, off-white background that lends itself to this … lightness. But also the books inner presentation, viewpoints and time, marked with section breaks, giving space for the ‘living’ and the dead.

One remembers haiku when reading Japanese literature:

The old pond

A frog jumps in

The sound of water

Stillness, viewing, disruption, an echo , right?

—reminding me of the final story in this book, where the author has Hirasaka from the studio take the child victim, Mitsuru, through a forest, to the top of the hill and place her hand on a cold smooth stone to make a wish, which she declines, as she feels there is no point since she’s already ‘dead’. Nonetheless, they practice shouting, to hear their echoes from a faraway place come back at them, and …

‘Amid the otherwise bare branches, she noticed several round clusters of leaves. Mistletoe, she thought as she snapped the photo. She watched as three birds took flight and soared into the clear sky. The cry of another bird pierced the limpid air.’

The Lantern of Lost Memories evokes tranquility, presence, intertwining nature with some of life’s larger questions, such as our existence, purpose, legacy, and whether we’d repeat, given a second chance, plus what we really cherish(ed).

In the bandit’s case, could he forgive his murderer and those, including his family members, who wronged him? Could he, in hindsight, treat others ‘beneath’ him, no matter their flaws, physical and otherwise, and himself, with more respect?

And what about the child victim? Life or death for her parents, now she has the ability to go back and change destiny?

These stories are gripping, perhaps not in the traditional suspense, horror or mystery sense, (albeit the characters’ spirits do re-visit, sometimes subconsciously or by the livings’— those from their previous lives, side), they’re certainly not forced, rather they emit a more mythical or fable like: ‘There was once a woman (e.g.) who … so let us learn from this tale’ type quality – the ex-nursery teacher with her wisdom and kindness against repeated rejection first story, being the leading example.

Sanaka’s characters rise and fall, their lives are disrupted, and it’s always interesting to read about other cultures’ views on, to borrow Donna Tart’s phrase: ‘The good life, what is the good life?’ as well as their take on the ‘after’ one, in this book’s case dipping in and out of slightly mythical worlds in order to, upon return, feel this life more deeply.

Plus, with translated works such as this, one can almost feel its pulse, both from the author’s fingers and the world opening up before them—to us—and that, my friends, coupled with Sanaka’s simple and reflective prose, to me is … pretty.

Stories on diverse people, places, landscapes; read about them here.

Copyright © 2025 Nitsa Anastasiades All rights reserved. Written content, photos and images may not be not be copied, shared or used without permission from the author.